Donnas Ojok and Kasirye Samuel

As humanity strives to attain freedom, especially that of expression, a perilous component in the name of hate speech is fast creeping in. In Africa, the vice has contributed to some of the darkest episodes of the continent’s history including the Rwandan genocide (1994) and Kenya’s post-election violence (2007/08), which claimed in short span approximately 800,000 and 1,200 lives respectively. In the newly independent South Sudan, the vice has been increasingly recognized as an early trigger-point for incessant ethnic and political tensions and conflicts that have been witnessed in the country since 2011. For purposes of contextual clarity, this paper focuses particularly on incidences of hate speech following the two major violence episodes in independent South Sudan in 2013 and 2016.

Generally, hate speech is taken to be communication or expression that denigrates people primarily based on their membership to a particular group whether ethnic, geographical, social or political. This can include any form of expression such as images, plays and songs as well as speech. Some definitions also extend the concept of hate speech to include communications that foster a climate of prejudice and intolerance,[1] incite violence, discriminatory treatment or offend human dignity of targeted person(s).[2] It is a term that is used to refer to verbal conduct – and other symbolic, communicative action – which willfully expresses intense antipathy towards some group or towards an individual based on membership in some group.[3]

While hate speech in South Sudan gained worldwide attention majorly after the December 2013 bloody violence episode, scholars such as Mahmood Mamdani have pointed out that negative ethnicity has historically been deeply entrenched in the socio-economic and political fabric of the country.[4] In this regard, he argues that the outbreak of violence in the country in 2013 was accompanied by various political motives including the motivation of the South Sudanese political elite to separate society into “us vs. them.”[5] This strategy, he argued, turned the crisis from political to ethnic. While it had been common for neighboring tribes to fight over resources in the past, these tensions were exacerbated by external influences that emphasized tribalism over common culture.[6] Mamdani also traces the roots of tribalism in South Sudan back to the British colonial era. The British solution to ruling a multi-ethnic state with mobile populations, he argued, was to draw hard territorial boundaries around identity. The system held ethnicity as an exclusive, as opposed to permeable, identity within a bounded homeland. The result, Mamdani asserts, was the politicization of ethnicity and fragmentation among groups, which directly contributed structural tension and mass violence.[7]

South Sudan, with its population of approximately 12 million people, is one of the most ethnically and culturally diverse countries of in the world. It has an estimated minimum of 163 distinct “people groups”, each consisting of numerous different tribes. Despite many commonalities between them, each ethnic group has a unique system of social culture, traditions, languages and identities.[8] This diversity possesses both a unique and colorful richness, but at the same time poses a threat to national unity and a common sense of identity.[9] To borrow a leaf from the description of ethnic identity in Kenya by Gichuhi and Njeri (2016), “tribal identification has been enculturated into the South Sudanese psyche to an extent that to truly know a South Sudanese, you need to connect him or her to an ethnic group.”

More recently, ethnically charged hate speeches is taking a toll on the country’s quest to stabilize and attain peace. In October 2016, for instance, a faction belonging to the Dinka ethnic group sent letters with graphic warnings of violence against the people from the Equatoria region and left it outside the gates of humanitarian organizations in Aweil West warning the Equatorians to leave or be eliminated.[10] This forced the United Nations to condemn the act and warn of the danger it poses to efforts towards restoration of peace and political stability in the country.[11] President Salva Kiir also reiterated similar message in his End Year (2016) address emphasizing that peace and stability will only be achieved when ethnically-inspired hate speech is severely eradicated.

Hate speech in the digital era

With the recent advent of social media, however, hate speech or more precisely, cyber hate, is taking new twists and turns. Online hate speech, for instance, is situated at the intersection of multiple societal and technological tensions. First, it is the expression of conflicts between different groups within and across societies. Second, it is a vivid example of how technologies with a transformative potential such as the Internet bring with them both opportunities and challenges. And finally, it implies complex balancing between fundamental rights and principles, including freedom of expression and the defense of human dignity.[12] These tensions tend to recur thereby increasing chances of repeat online hate speech as observed in Kenya during the 2013 general elections despite the devastating post elections violence of 2007/08.[13]

In South Sudan, the situation is getting worse as both South Sudanese at home and abroad embrace social media as a tool for venting out tribal grievances, mostly between the Dinka and the Nuer, the two most dominant tribes in the country. According to Theo Dolan of US PeaceTech Lab Project, "hate speech can originate through a diaspora community in the U.S. or Australia, and very quickly cross borders and oceans through different platforms from mobile phone calls, on family calling another or through WhatsApp…It gets very quickly around so that with friends or family calling each other from the U.S. to South Sudan, that inclination can very quickly spread…It doesn't necessarily rely on just internet access".[14] It is thus important to recognize that online hate speech has a real negative impact towards ushering in peace and stability and promoting socio-economic development.

The PeaceTech Lab project recently published a comprehensive analysis of the relationship between social media and conflict in South Sudan. The lexicon, which is a compendium of hate speech terms in South Sudan identifies and contextualizes some of the words that perpetuate hate speech in South Sudan.[15] The resource is built on the premise that rather than simply acknowledging that hate speech exists, sensitizing people about it could help to prevent violence.

To fully analyze hate speech, it is crucial that we draw on some relevant theoretical contextualization. Before delving into the theory, it must first be emphasized that language in most of these societies including South Sudan is not only is a significant variable in ethnicity but a key determinant of someone’s belonging. Language is also a key tool for organizing people and directing their behavior.[16] Understanding the relevance of language defining culture and identity thus leads us to the Speech Act Theory (SAT) postulated by J.L Austin in 1975.[17] SAT explains how language (spoken or written) could be used to achieve preconceived intentions.[18] Speech Act Theory argues that to say something is to do something. In other words, “we do things, not only say things, with words”.[19] For instance, in a wedding when a man says, “I do,” he is not only describing his mental state that he is willing to marry the woman, rather, at that moment, his speech is an act of taking the woman as his wife.[20]

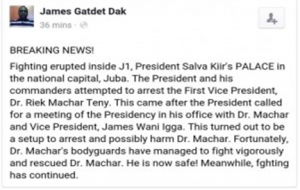

What this theory offers in the context of South Sudan is that the prevailing atmosphere polluted by hate speech is a step in the wrong direction towards restoring law and order, peace and stability and long term development in the world’s newest country. Indeed, hate speeches in South Sudan have on many occasions been accompanied by vitriolic outburst of violence by one ethnic faction against the other. For example, in July 2016, when President Kiir and Vice President Riek Machar were holding a meeting in the State House, exchanges of politically instigated hate speech by presidential guards (mostly Dinka) and vice-presidential guards (mostly Nuer) soared and culminated into physical and gun violence which engulfed the entire country within a few hours and led to deaths of hundreds and subsequent collapse of the Transitional Government of National Unity (TGoNU) established in 2015 under the auspices of IGAD. Shortly after the fierce battle between the two factions allied to President Kiir and First Vice President Machar respectively at the Presidential palace, James Gatdet Dak, Machar’s spokesperson posted this on Facebook:

This was shared several times on social media and it is undoubted that it helped to fuel the violent encounters between SPLM (IG) and SPLM (IO) that led to the deaths of over 300 people and displacement of thousands of South Sudanese.

While indeed the cause and proliferation of the conflict in South Sudan remains an intricate political economy question, it is clear that ‘the deeply entrenched mistrust and paranoia accelerated by social media have created the conditions where an unfounded rumor or accusation could trigger much larger conflagration’.[21]

To a large extent, propagating hate messages in South Sudan is now turning into what political economy scholars refer to as a demonstration of violence capacity (North, Wallis, Webb and Weingast, 2014). According to these theorists, political economy operates behind the shadows of violence, with one who is able to exhibit an exceptional show of violence capacity emerging the winner or at least giving them the opportunity to partake in resource allocation and power sharing. In the context of South Sudan, for example, this phenomenon can best be demonstrated by social media posts by Gordon Buay, South Sudan’s deputy ambassador to the United States, on December 13, 2014 when he opined “…this is not 1990s factional fighting. If Riek Machar wants war we will give him the real war that will involve aerial operation such as MIG jets, gunships including amphibious tanks. Riek and his rebel terrorists will see a fight in the dry season that they have never seen before. It is better if they accept peace and surrender to us.”

It is important to note that this was posted at the time when negotiations to establish the TGoNU was underway in Ethiopia. When the ambassador was contacted by Anadolu Agency, a Turkish news outlet, he dismissed the idea that his utterances as a diplomat could fuel war or sow lasting hatred among the people instead arguing that “it would be unfair if someone accuses me of negative propaganda yet I am doing my role. Through social media, am fighting enemies of peace that have taken arms against the legitimate government. I cherish and uphold the fact that sovereignty is vested in the people of South Sudan, President Salva Kiir and his entire government that were given the mandate by the people through elections, and it is my obligation to defend the constitution by all means.”[22]

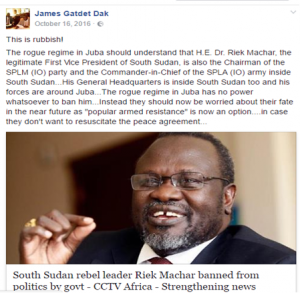

In response to a recent article by CCTV Africa, James Gatdek Dak, the SPLM (IO) Spokesperson had this to say on his social media platform:

Why cyber hate speech is bad for peace building and development in South Sudan

There are many ways in which digitized hate speech affect peace building efforts in an already fragile post-conflict state like South Sudan. In fact, there is a dearth of empirical information on impact of digitized hate speech especially in the African context in particular. For example, the work of Gichuhi & Njeri (2016) provides some illuminating data and context from the Kenyan experience. The authors established that over half of the respondents (50.5%) stated that reading hate messages targeted at their own ethnic group on the social media made them feel bad about themselves, while 47.9% indicated that it did not. A great majority (86.7%) also indicated that reading hate speech messages on social media made them feel bad about the authors of such hate messages. At least 90.7% of the respondents believed that hate speech messages on social media influence people’s judgement about the target ethnic groups. Whilst this data is from the Kenyan context, it provides a vivid picture of the likely cost of cyber hate on a broader scale.

A local advocacy platform in South Sudan, the Community Empowerment for Progress (CEPO) recently conducted a research and found out that three-quarters of South Sudan’s young people have access to Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp, and that most have posted hate speech that may have in one way or another fueled the conflict. Edmund Yakani, CEPO’s ED, reports that 60 percent of South Sudanese social media users are engaging the platform to propagate hate speech that is essentially tribal and “incites violence.”[23]

Hate speech in South Sudan spreads like wild fire because in situations of uncertainty, fragility and hopelessness, people often do not take time to verify the truthfulness of information and can easily be influenced to act by rumors and false news. This is further exacerbated by the high rates of illiteracy in the country which currently stands at more than 70%. Illiteracy plays a role in the proliferation of fake news because of the information trickle down process which gets distorted and misinterpreted along the way. When the few South Sudanese elites who are also the ones who have access to social media engage in the digital space either constructively or destructively, the information seeps in to the rest of the country and it’s picked up through word of mouth by the local people at grassroots. When it’s a destructive social media post, the illiterate masses that are also unable to verify the authenticity of the information because there are very few conventional media outlets like radio and TV are easily compelled to not only spread the misinformation but also act, in the process hindering all possibilities for peacebuilding.

The way forward: Transcending the hate speech vice

As posited by Nenad Zivanovski, any “discussion on the relationship between freedom of expression and hate speech in a democracy raises a series of polemical questions: Are the two in conflict? Does the right to free expression include the right to offend? Does banning hate speech equate to state censorship of opinions and attitudes?”.[24] Understanding these questions in the context of South Sudan provides crucial points of analysis. One way of fighting hate speech is strengthening the legal framework within which social media operates. Being a recent phenomenon, all countries, including the already advanced ones are still grappling with the legality of social media usage. This means that for countries like South Sudan, the situation is even more complicated. But considering the wildfire effect of hate speech being propagated by social media, international organizations must quickly work with the South Sudanese government to quicken the establishment of a legal framework for addressing cyber hate.

But in a country like South Sudan where the rule of law is already weak, addressing the legal gap of itself may prove insufficient. What international organizations can quickly do is to also generate new knowledge on hate speech and share it widely amongst the South Sudanese people, both at home and in the diaspora. This can involve the use of the same social media platforms being engaged to popularize hate speech to sensitize people about the vice. Some few organizations like the US Center for Peace through their Peace Lab in Nairobi has already invested considerably in research and producing a lexicon of hate speech terms used by South Sudanese. The #defyhatespeechnow movement have also played recognizable role in the campaign against hate speech. Such efforts should be complimented by a more robust intervention by organizations that put peace, stability and development at the core of their work.

But more importantly, those who engage on social media must take deliberate attempts to counter hate speech by not sharing it, demonizing it, and/or raising critical voices against such hate relate posts and messages on social media. This can only be successfully done if South Sudanese social media users have a full grasp of knowledge of hate related speeches and posts, and deliberately act to avert it. This can be complimented by conventional media platforms such as radios, TVs and print newspapers engaging in concerted effort to fight hate speech. They should take center-stage in making sure that access to authentic and unifying information underpins their journalistic practices.

Like never before, the South Sudanese elites (both at home and beyond) and those interested in progress in South Sudan have a crucial role to play to re-direct the country by defying hate speech and promoting messages that promote peace, unity and development.

Ojok Donnas is a Programme for African Leadership fellow and an alumnus of the London School of Economics.

Kasirye Samuel is a Programme Manager at the Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung – East African Regional Office.

References

[1] See, Introduction To Hate Speech On Social Media Community Empowerment for Progress Organization (CEPO), Juba & r0g_agency for open culture and critical transformation / Berlin https://defyhatenow.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/defyhatenow_whatishatespeech_JUL27.pdf (accessed April, 2018)

[2] Stakic, 2011

[3] Simpson, 2013

[4] Allyson Hawkins “South Sudan: The Road to Civil War” with Professor Mahmood Mamdani” https://sites.tufts.edu/reinventingpeace/2016/10/04/south-sudan-the-road-to-civil-war-with-professor-mahmood-mamdani/

(Accessed April, 2018)

[5] Ibid

[7] Ibid

[8] LeRiche, M. & Arnold, M. (2013), South Sudan - From Revolution to Independence, Oxford University Press 6 Global Security

[9] Ibid

[10] See, for example, http://www.africanews.com/2016/10/27/hate-speech-in-south-sudan-worrying-the-morning-call/ (Accessed January, 2017)

[11] UN News Centre (2016), South Sudan: UN human rights chief warns of ‘alarming rise’ in ethnic hate speech.

[12] Countering Online Hate Speech, UNESCO

[13] Gichuhi & Njeri (2016), Digitized Ethnic Hate Speech: Understanding Effects of Digital Media Hate Speech on Citizen Journalism in Kenya

[16] Ayeomoni, O. M., & Akinkuolere, O. S. (2012) A Pragmatic Analysis of Victory and Inaugural Speeches of President Umaru Musa Yar‟ Adua, Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 2(3), 461-468.

[17] Austin, J. L. (1975) How to do things with words (Vol. 367) Oxford University Press.

[18] Ibid

[19] Ibid

[20] Ibid

[21] See https://www.ssrresourcecentre.org/2016/07/12/facebook-and-social-media-fanning-the-flames-of-war-in-south-sudan/ (accessed April 2018)

[22] For details visit http://aa.com.tr/en/africa/social-media-used-to-fuel-south-sudans-civil-war-/655493 (accessed April 2018)

[23] Parach M (2016) Social media used to fuel South Sudan's civil war (http://aa.com.tr/en/africa/social-media-used-to-fuel-south-sudans-civil-war-/655493, accessed April 2018)

[24] Nenad Z (2016) Hate speech, free speech Hate-Speech International (https://www.hate-speech.org/hate-speech-free-speech/ accessed April 2018)